WAKE THE STONE MAN - excerpt

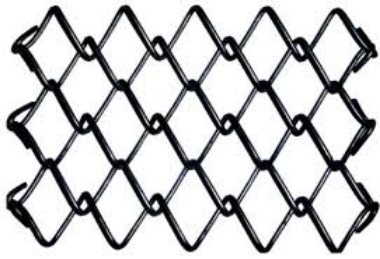

The first time I saw her she was climbing over the top of the chain-link fence of the residential school. The tops of her fingers curled over the metal fence were dark, but the palms facing me were pink. Pink as mine. I wanted to look down at mine to check, but she was staring at me. I waited for her to speak. She didn’t.

I could have kept walking, should have kept walking down the path to the building where I took my ballet lessons. Didn’t have to stop just because she was staring at me. But I stopped and watched her.

“Nakina!” A flash of black behind her as a nun moved towards the fence. Black and white, and the glint of silver from the buckle of a belt. “Get off that fence.”

Thwack of metal as the buckle hit the fence.

I ran. I ran down the path, away from the residential school, ballet shoes bouncing off my back. I was on the other side of that fence and I didn’t have a strap coming down on my back but I ran like hell. She didn’t move.

After that day I looked for her. I wanted to ask her something. I wanted to ask her where she was going that day she tried to escape over the fence. Every time I went to my dance class I stopped outside the fence to see if I could find her.

Some people called St. Mary’s the residential school. My mom called it the orphanage. I asked her what it meant and she said it was a place for orphans, and I said what’s an orphan and she said someone whose parents are dead, and I said are all those Indian kids’ parents’ dead and she said no. I didn’t get it.

The place was huge. Bigger than the church and bigger than City Hall. A red brick building four storeys high, with rows and rows of narrow windows and a porch on the second floor. Indian kids lived there. Mostly Indian, looked like hundreds of them. And the nuns who ran the place were always yelling and making them line up. Nuns in long black robes screaming their heads off. Scary.

I stopped every time I walked by. I saw kids playing marbles under a statue of Jesus nailed to the cross. In winter I saw kids playing hockey on the rink they’d made in the field behind the school. In spring I saw kids working in the gardens and lining up to go in for mass when the bells in the chapel rang. But I didn’t see her.

***

It was two years before I saw her again. I’d been sick the first week of high school so I had to go to the office to register. I was waiting outside the principal’s office feeling so nervous I thought I would puke, when she walked over, sat down beside me and said, “Hi,” just like that. Hadn’t seen her since the day she was trying to escape from the residential school, and she looked right at me and said “Hi” like we were best friends or something.

“Nakina Wabasoon?” The principal stuck his head out of his office. “Come on in.” After a couple of minutes the principal came back out and nodded to me.

“Molly Bell? Come in.”

I went in and sat down in a chair beside Nakina. The principal was short and fat and had a wonky eye so you never knew if he was looking at you.

He went through a lot of stuff about teachers and lockers and wings and periods and I kept nodding my head like an idiot. I was nodding and smiling and wondering which one of his eyes was the real one and which was the glass one, and I didn’t know what the hell he was saying.

As we left the office I was about to tell Nakina that I didn’t have a clue where we were supposed to go and she said, “Follow me.”

So I followed her down the corridor. I followed her to our lockers. I followed her to our homeroom. And after that day, I just kept following Nakina.

We were both in Mrs. Kouie’s English class. English for girls in secretarial arts and cosmetology. Cosmetology—I remember getting real excited about that till I found out it had nothing to do with the theory of the universe.

I liked English. Liked books. Never told anyone but my favourite place was the Brodie Street Library. I used to sit at the table under a stained glass window with two big heads—Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare. I liked sitting with Charlie and Billy.

Mrs. Kouie loved words, metaphors and allegories. She loved poets. But most of all Mrs. Kouie loved Leonard. Mrs. Kouie let us borrow her poetry books, and on our lunch break Nakina and I would find an empty classroom and read Leonard. Then we wrote the poems in chalk on the board to see the shape of the words of Leonard Cohen.

Nakina discovered The Spice-Box of the Earth and began to read aloud “For you I will be a Dachau Jew and lie down in lime with twisted limbs...”

“That’s me,” she said.

“He’s writing about Jews. Are you a Jew?”

“He’s writing about the holocaust.”

“Are you a holocaust Jew?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Get out.”

“I am.”

“Get out.”

“He means Jews metaphorically.”

“You’re a metaphorical Jew?”

“Don’t be an ass, Molly.”

“Seriously, I don’t get how you are metaphorically a Jew.”

“I’m Indian. Anishinaabe.”

“So.”

“So we’re like the Jews. The Jews of Canada.”

“You’re a Canadian, Indian Jew. OK, so what about the holocaust?”

“Do you even know what a holocaust is?”

“Sure, what happened to the Jews in the war.”

“No. The word. Do you know what the word means?”

I shrugged.

“Genocide. The slaughter of a race. What they did to me.”

“Come on. Who slaughtered you?”

“The residential school.”

“I don’t get it. How?”

“Red kids in—white kids out. Genocide.”

I got quiet after that. Didn’t know what to say. Just got up and went back to class. Couldn’t concentrate on anything all afternoon.

Red kids in—white kids out. I kept thinking about the first time I saw Nakina, climbing the chain-link fence trying to escape with the belt coming down on her back. Leather belt coming down to whack the Indian right out of her.